THE MEEKER MASSACRE AND THE BATTLE OF

MILK CREEK

The rush to

Colorado began in the turbulent days of the Kansas-Nebraska Territory

preceding the Civil War. After finding gold at Cherry Creek (present day

Denver) miners moved on to establish the

legendary mining towns of Central City and Blackhawk.

In the 1870’s during

the economic depression following the Civil War, white miners and

settlers in covered wagons, on horseback, and on foot, encouraged by the

Homestead Act, and

drawn by news of mineral wealth, again followed the long trails to gold

in the Colorado mountains. By now the Union Pacific Railroad was

completed and others were penetrating the Front Range of Colorado.

Miners rushed west

over the high passes where they created other legendary mining towns in

the areas of Summit County, Leadville and Silverton. These mining

successes heavily penetrated Ute territory. The Ute Indians, who

considered the whole of Colorado their home for generations, resented

their diminishing hunting ground and the white men resented and

distrusted the Indian.

Colorado Statehood

came in 1876. Newspapers of the day demanded the removal of Utes off of

land that could be mined, farmed or ranched. The attitude of many

Coloradans, at the time, was, “The only good Ute was a dead Ute”.

Into this mix of

tensions was injected Nathan C. Meeker who sought and was appointed

Indian Agent at the White River Indian Reserve in 1878. His actions were

to precipitate a cultural and military explosion.

Meeker was an

idealist who owned a store in Ohio and he was also a newspaper farming

reporter. Later Meeker moved to New York City where he worked for

Horace Greeley on the New York Tribune. Meeker asked Greeley for his

help in starting a utopian colony. They conceived of the Union Colony

(present day Greeley, Colorado) which was to be located in the eastern

foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Though the project was ultimately a

success, Meeker believed he had failed and that he owed Greeley’s heirs

money. He managed to obtain the job as Indian Agent at the White River

Ute Reserve (Reservation) in an effort to pay off the debt. His contact

with Indians had been minimal and when he finally did meet the Ute

people he did not listen to his wards, nor was he sensitive to their

long established cultural patterns.

Meeker, unwisely, in

retrospect, brought his wife Arvilla, daughter Josephine, his young

master farmer, Shadrach Price, Flora Ellen Price and their two children

Johnny and May plus other working men from the Union Colony to help set

up the agency and begin the farming at Powell Park.

He had moved the

agency 11 miles down the White River to Powell Park which is three miles

west of present day Meeker. Both the move and Meeker’s ideas were

unpopular with the Indians since they pastured their large herds of

ponies in the lush meadows of Powell Park and proved their worth by

racing their ponies and hunting for their families; just as the Ute

women job was to gather native plants, do some gardening, feed their

families and move their camp.

At the time, White

River Ute leaders were Johnson (Canalla or Canavish), Douglas (Quinkent),

Colorow, a Comanche and Jack (Nicaagat), who was leader of the younger

men. Chief Ouray, famous as the government appointed leader and chief

of all the Ute tribes in Colorado, believed in ultimate peace and

compromise with the Federal Government; a belief based on his visit to

Washington D.C. after the Civil War and his having viewed 200,000

American troops camped around Washington. Ouray was, in fact, only

leader of the Uncompahgre Ute Tribe near present day Delta. His views

of coexistence were not accepted by many other Ute tribal leaders,

although they tried to avoid arguing with him as he was both intelligent

and tough.

To gain some

understanding of Meeker’s problems would involve knowing that at the

time Meeker was appointed, the Bureau of Indian Affairs adapted a strict

policy that included the provision that if adult Indian males did not

participate in agricultural efforts, their food, given to them by the

government, would be withheld. The Utes did not believe Meeker as they

knew this mandate was not in their treaty. There began a complete lack

of trust on the part of the White River Utes who believed Meeker was

not telling the truth regarding such policies. Although, Meeker induced

the Indians to help his men build an irrigation ditch, which is still

being used in Powell Park today; this did not mean the Utes wanted to

farm, furthermore it has been related that Meeker paid the Utes for this

work.

Meeker’s imperative

was to teach the Utes to become self-sufficient farmers. When the Utes

would not stay on the reservation and farm, but instead continued

following their age old lifestyle of extended hunts, Meeker tried to get

them to stay on the reservation and work; at first in a kindly way and

as that failed he applied more pressure.

He threatened to

have the troops from Ft. Fred Steele at Rawlins, Wyoming come put the

Utes in chains and take them away to the Indian Territories in Oklahoma.

A threat he did not have the authority to make. The Utes did not

believe that he had the authority to do this and Meeker was widely

accused of lying to them in this regard.

The newly formed

State of Colorado and the Federal Government did not have coordination

regarding the situation at the White River Agency. Meeker had advised

the Major Tipton Thornburg, at Fort Steele, and the Bureau of Indian

Affairs that he would need military presence to achieve the policy of

strict agriculture work. His request was ignored. However, the

citizens of northwest Colorado, when requested from the state, received

military support from US Army units headquartered at Ft. Garland. These

soldiers reported to a different chain of command from those at Fort

Steele where Agent Meeker, by policy, sought support.

Citizens from around

Beyer’s Canyon near present day Kremmling, Colorado complained of the

White River Utes being off the reserve and causing problems. Meeker

asked Major Thornburg, commandant of Ft. Fred Steele, to investigate and

Thornburg found little cause to be alarmed. However, it must be noted

that Thornburg in a letter to Gen. George Crook, commander of the Dept.

of the Platte at Omaha Barracks stated he had never received any orders,

from his superior, to cause the Indians to remain on the reservation at

the request of the agent, but that he was ready to send his men if

ordered to do so.

The Governor of

Colorado asked for military presence from Fort Garland. At his request

a cavalry unit of Buffalo Soldiers, under Captain Dodge, were stationed

at Troublesome Creek, east of present day Kremmling, Colorado; in the

summer of 1879.

In

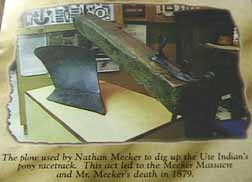

the late summer of 1879, the situation began to come unraveled. Meeker,

believing the ponies to be the major problem had conceived the idea of

plowing up the Ute racetrack. At this point there is a lot of

conjecture about what happened that precipitated the following events.

One story is that upon hearing about his idea Jane, Arvilla’s

housekeeper, confronted him about plowing up her land. The frustrated

Meeker argued with her and told her that the land did not belong to the

Utes and they could lose it if they didn’t obey him, which, of course,

he realized, immediately, had been a serious mistake. Another story

relates that Jane turned her back and

walked away, which was frustrating to the agent. Yet another account,

according to Josie Meeker, Mr. Meeker built Jane a house and dug her

well in compensation for the land. Whichever is true, Shaman Johnson

came to Meeker furious about Meeker’s statement to Jane and/or the

plowing of the racetrack; the two argued. Some stories related that

Meeker, told Johnson he would need to kill half the ponies, while he,

Meeker, would have Shadrach Price plow up the Indian race track. The

fact is Meeker did indeed have Mr. Price start plowing until one of the

Indians shot over his head. Another version is that Johnson and Meeker

started arguing about the irrigation ditch, the plowing and the ponies;

whatever the argument was about; there was shouting, according to

Meeker’s wife Arvilla’s account, but she made no mention of Meeker being

accosted. Meeker said Johnson shoved him against the wall of the agency

and then over the hitching rail, where he sustained injury. The Ute

Indians say this never happened. This argument appears to be the final

insult as far as the Indians were concerned, as their ponies were their

wealth and they believed the reservation was theirs.

In

the late summer of 1879, the situation began to come unraveled. Meeker,

believing the ponies to be the major problem had conceived the idea of

plowing up the Ute racetrack. At this point there is a lot of

conjecture about what happened that precipitated the following events.

One story is that upon hearing about his idea Jane, Arvilla’s

housekeeper, confronted him about plowing up her land. The frustrated

Meeker argued with her and told her that the land did not belong to the

Utes and they could lose it if they didn’t obey him, which, of course,

he realized, immediately, had been a serious mistake. Another story

relates that Jane turned her back and

walked away, which was frustrating to the agent. Yet another account,

according to Josie Meeker, Mr. Meeker built Jane a house and dug her

well in compensation for the land. Whichever is true, Shaman Johnson

came to Meeker furious about Meeker’s statement to Jane and/or the

plowing of the racetrack; the two argued. Some stories related that

Meeker, told Johnson he would need to kill half the ponies, while he,

Meeker, would have Shadrach Price plow up the Indian race track. The

fact is Meeker did indeed have Mr. Price start plowing until one of the

Indians shot over his head. Another version is that Johnson and Meeker

started arguing about the irrigation ditch, the plowing and the ponies;

whatever the argument was about; there was shouting, according to

Meeker’s wife Arvilla’s account, but she made no mention of Meeker being

accosted. Meeker said Johnson shoved him against the wall of the agency

and then over the hitching rail, where he sustained injury. The Ute

Indians say this never happened. This argument appears to be the final

insult as far as the Indians were concerned, as their ponies were their

wealth and they believed the reservation was theirs.

The

Utes, were further upset because Meeker sent a telegram to Washington

D.C. and they could not get Meeker to tell them the content of the

message.

Meeker’s telegram read, “I HAVE

BEEN ASSULTED BY LEADING CHIEF, JOHNSON, FORCED OUT OF MY HOUSE AND

INJURED BADLY, BUT WAS RESCUED BY EMPLOYEES. IT IS NOW REVEALED THAT

JOHNSON ORIGINATED ALL THE TROUBLE STATED IN LETTER SEPT. 8. HIS SON

SHOT AT PLOWMAN AND OPPOSITION TO PLOWING IS WIDE, PLOWING STOPS: LIFE

OF SELF, FAMILY AND EMPLOYEES NOT SAFE: WANT PROTECTION IMMEDIATELY:

HAVE ASKED GOVERNOR PITKIN TO CONFER WITH GENERAL POPE. N. C. MEEKER,

INDIAN AGENT.

Employee,

Fred Shepard, had written a letter to his mother, which had been picked

up just before the outbreak of hostilities which said, “IN REGARDS TO MY

GETTING OUT OF HERE SOON, I HAVE NOT FELT AS IF I WAS IN ANY DANGER SO

FAR AS MY LIFE IS CONCERNED SINCE I HAVE BEEN HERE ANY MORE THAN EVER I

DID IN YOUR DOOR-YARD. I DON’T BLAME THE UTE FOR NOT WANTING HIS GROUND

PLOWED UP. IT IS A SPLENDID PLACE FOR PONIES AND THERE IS BETTER

FARMING LAND, AND JUST AS NEAR, RIGHT WEST OF THIS FIELD, BUT IT IS

COVERED IN SAGE BRUSH. DOUGLAS SAYS HE WILL HAVE THE BOYS (The Ute

Indians) CLEAR THE SAGE BRUSH IF N. C. (Nathan Cook Meeker)

WILL ONLY LET THE GRASS ALONE. BUT, N. C. IS STUBBORN AND WON’T HAVE IT

THAT WAY AND WANTS THE SOLDIERS TO CARRY OUT HIS PLANS. DON’T KNOW HOW

IT WILL TURN OUT, BUT YOU CAN BET IF THEY TOUCH ANYBODY IT WILL BE THE

AGENT FIRST.” (Mr. Shepard died in the conflict).

The

subsequent action of the government in sending Major Thornburg and his

troops from Ft. Steele only upset the Indians further, as they did not

want soldiers on their reservation. The soldiers did not want to be on

the reservation anymore than the Indians wanted them there; after all,

this was after the Little Big Horn and the Sand Creek Massacre; but

orders were orders.

Jack and some of

his men met Thornburg at Fortification Creek and asked what he was going

to do. All Thornburg could tell them was that he had to assess the

situation before he could answer. Jack again met Thornburg at near

Peck’s Trading Post (at present Craig, Colorado) and Thornburg,

when pressed for information, could only give the same answer. Around

this time the Utes started having war dances in the evening at the

agency.

Meeker had

certainly been right when he asked Thornburg to investigate and even

close Peck’s Trading Post because as there was little or no coordination

between the Indian Service and the military; no one was policing Peck’s

store where Jack bought 10,000 rounds of ammunition for rifles better

than those carried by the U.S. Army. Jack bought these at the same time

the soldiers were camped on the Yampa River, in the same valley as

Peck’s Trading Post. Thornburg

unwisely had not shown interest in Meeker’s request when it was made to

him earlier in the summer. Meeker just as unwisely refused to meet

Thornburg at edge of the reservation, but in that desperate day, history

records him to have said that to leave the Powell Park site would have

left it to likely looting by the Indians.

On

September 29, 1879 an unfortunate meeting between soldiers and the Utes

at the crest of a ridge just after they crossed Milk Creek into the

reservation was sparked into a battle by a single gun shot; by which

group is unknown. Major Thornburg was killed while the soldiers were

fighting their way back to the circling mule wagons near Milk River

(Creek). Trenches were hurriedly dug and the soldiers were then

pinned down. The Indians were killing horses to keep the soldiers from

getting away and the soldiers were piling those dead horses between

themselves and the bullets. Theirs was a harrowing tale for the men and

for the help who arrived in the form of Captain Dodge and his few

buffalo soldiers, days later.

When the Buffalo

Soldiers arrived they walked their horses through the Indians and

brought more food and ammunition to the entrenched soldiers. It is

speculated that he reason for their being able to come in so easily was

because they were about the same size as a forward scouting party and

the Indians were probably checking to see if there were more troops

behind them. Among the Buffalo Soldiers was Sgt. Johnson who took the

dangerous task of getting water from Milk Creek. Sgt. Johnson is the

first black man to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor. There were

11 men in that company who received Medals of Honor for saving each

others lives.

Joe Rankin, the

scout, left the circle of wagons in the night and rode an epic 158.7

miles north to Fort Steel in twenty eight and a half hours; only

changing horses twice! He was carrying a message from Capt. Payne which

included this statement, “....AFTER A DESPERATE FIGHT SINCE 12:00 N.

WE HOLD OUR POSITION AT THIS HOUR”. These men were truly in a

terrible position and worked hard to keep each other alive. Col. Wesley

Merritt from Fort D.A. Russell gathered troops by train and started

south to come to the rescue. His march was such that it was used as an

example for years to come at West Point.

On the same day as

the battle the Utes had attacked the agency. Meeker ignored warnings

from Tom and Billy Morgan, ranchers who raced horses with the Utes, and

warnings from the Indians themselves; Meeker had signed a death warrant

for the 11 men at the agency including himself. The Ute burning of the

agency, and the capture of the women and children was also an

excruciating travail. It is assumed that it was Ouray’s sister, Susan

who sent a rider to Ouray to get help.

Chipeta, Ouray’s

wife, sent riders to find Ouray who was hunting on Grand Mesa and sent

the news to the Los Pinos Agency. Ouray, in turn, sent Mr. Joseph W.

Brady to Colorow and Jack at Milk Creek to stop them from fighting. On

October 8, Brady got there right at the time Merritt and his troops

arrived to rescue the trapped men. Merritt sent the men back to their

various forts and then rested at Milk Creek where he built up his troops

to over a thousand men.

A week later,

Merritt went over Yellow Jacket Pass and into Powell Park for the first

time. Needless to say, the White River Agency was a smoldering ruin and

the men’s bodies were still on the ground. Merritt and his men buried

the men and then were ordered not to chase the Indians any further, but

to stay in the vicinity.

Interior Secretary

Schurz had Merritt stop at Powell Park instead of pursuing the fleeing

Utes and at the same time set “General” Adams, a special Agent of the

Secretary, the task of rescuing the captives. Adams two companions

were Captain Cline, who had served as scout for the Army of the Potomac

and Mr. Sherman, Chief Clerk of the Los Pinos Agency. The White River

Utes were not happy about giving up the women and kept Adams in debate

until Susan broke into the tent and convinced the braves their safest

path was to send the captives home. Mrs. Meeker said, “We owe much to

the wife of Johnson. She is Ouray’s sister and like him she has a kind

heart.” The women were finally freed after 23 days of harrowing

captivity.

Col. Merrit (later

General Merrit) and his men spent the winter of 1879-1880 in tents and

built the cantonment (a temporary camp), at the site were Meeker now

stands, in the spring of 1880. The camp was called “Camp on the White

River”.

The log buildings

which now house the White River Museum and one private dwelling were the

officer’s quarters, housing two officer’s families in each building.

The area where the Rio Blanco County Courthouse and the Meeker

Elementary School now stand was the parade ground. Across the parade

ground facing the log buildings were the soldier’s adobe barracks which

is now the downtown portion of the town. Take note of the long narrow

buildings such as the Meeker Drug Store as it is on the land of one of

those long narrow barracks.

The extensive

collection, in the White River Museum, has been donated over a number of

years by the people who pioneered this valley after the Utes were

removed to Utah following Ouray’s death. The rest of the collection in

the other museum building, called The Garrison, has also been donated

and pertains to artifacts about the Milk Creek Battle and the Meeker

Massacre.